Back to home page

Back to home page

This timeline of radio navigation was originally concieved for and on display at the RIN@75 anniversary exhibiiton 'Waves of Navigation'. The timeline includes key RIN members’ work towards the amazing reality that there are now almost as many navigation receivers in the world as there are people! Keep an eye on this page for more upcoming content.

Origins & The Daventry Experiment

The origins of radio navigation can be traced to scientific developments in the 19th century. Early electromagnetic radiation experiments by Heinrich Hertz and James Clerk Maxwell confirmed that metallic objects reflect electromagnetic waves. In 1904 “radar” technology , though not range measurement, was first demonstrated by Christian Hülsmeyer in Germany.

Radio-assisted navigation was famously credited to Sir Robert Watson-Watt and Arnold Wilkins with the 1935 Daventry Experiment. Originally, the Air Ministry invited Watson-Watt to look into developing a 'death ray' using radio waves. Dismissing the 'death ray' on technical grounds, Watson-Watt and Arnold Wilkins instead successfully demonstrated that radio waves could be bounced off aircraft up to eight miles away, detecting the metal body via means of scattered or reflected electromagnetic radiation.

With war looming and a 1000 strong Luftwaffe fleet, RAdio Detection And Ranging (RADAR) was quickly prioritised by the UK government. By May 1935, Watson-Watt and his team were building 240ft wooden receiver towers and 360ft steel transmitter towers at Bawdesy Manor. Just eighteen months later, on 24 September 1937, RAF Bawdsey became the first fully operational radar station in the world. By 1939 a chain of radar stations was in place around the coast of Britain.

Patent application by Robert Watson-Watt (RIN presidnt 1949-1951

QM, Decca and Loran-C

The early research for the Decca Navigator system was done in the USA, before being further developed by Decca in the UK from 1939.

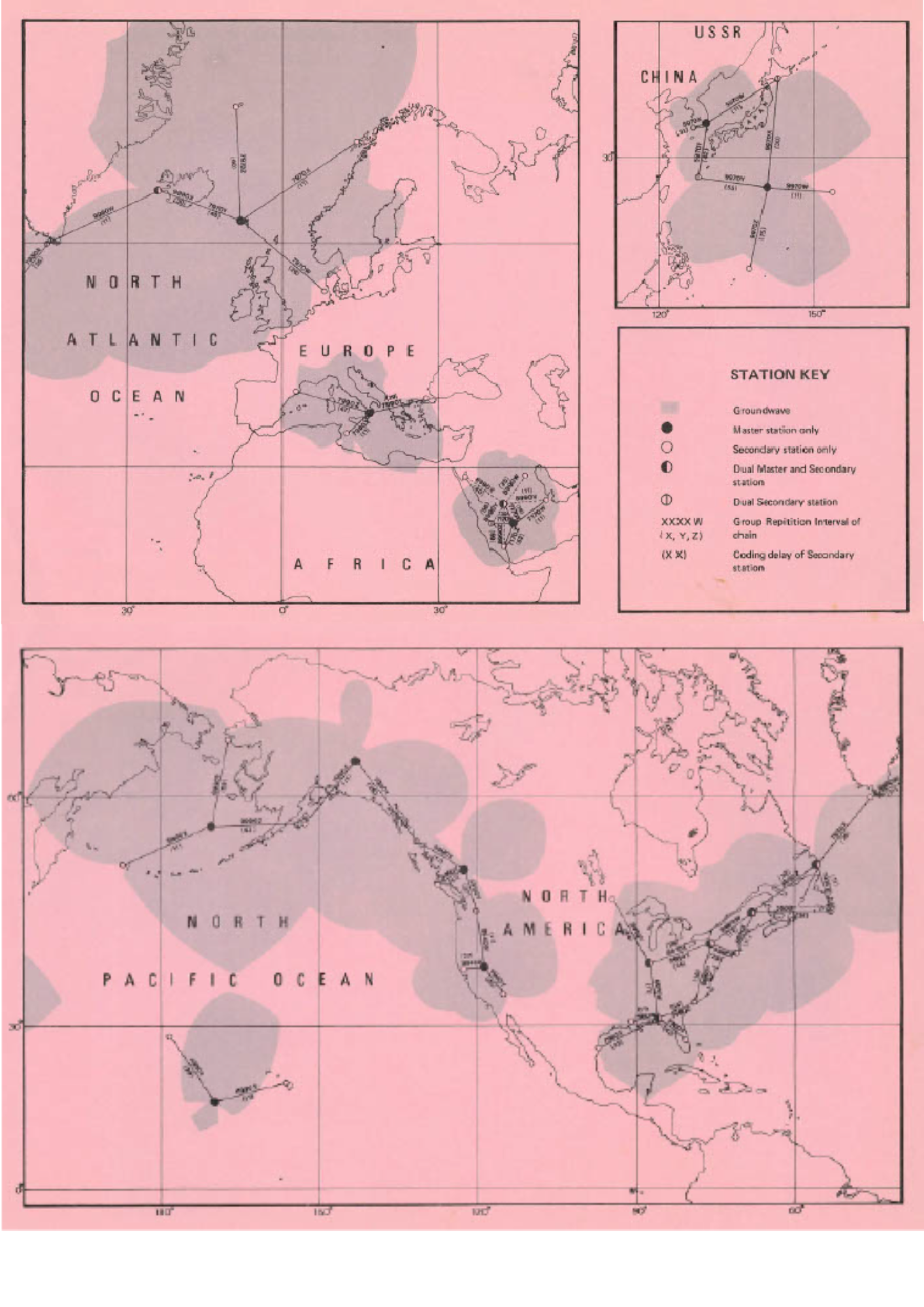

In 1944 the type QM system (later known simply as Decca Navigator) was first used for mine clearance operations.Technically, Decca was a hyperbolic radio navigation system operating at low frequencies (85 – 127.5 kHz) which had a key advantage: long-range use at sea. Decca used static phase locked radio transmitters. The receivers compared the phases of the different signals detected to determine range.

After the war the Decca Navigator system became widely used in ships of all sizes, reaching a peak of 30,000 marine users in 1970. Loran was developed and maintained in the US for nearly 40 years, and had some input from the Gee system used in World War 2. All Loran chains used the same low frequency (90 – 110 kHz) ground wave. Different signal repetition rates of the master and secondary station sequence distinguished between chains.

Decca, Loran-C and Transit Receivers

Our story of “The Daventry Group” begins in the late 1970’s. Following initial work with Decca and Loran units, Polytechnic Marine developed a range of Transit Satellite receivers for maritime applications. A Z80 eight bit processor tracked the satellites as they passed overhead. The same processor was used subsequently for calculating the position. The receiver was quite innovative in that it included inputs for dead reckoning sensors such as compasses and log. These were needed to fill the gaps during the time that Transit satellites were not visible to the receiver.

Later versions of this receiver included support for Loran and Decca too.

However, GPS was coming and everything was about to change.

Transit and Initial GPS Operations

The space race was on! 1958 saw the Doppler shift from the transmitted signal of Russia’s Sputnik-1 analysed to derive its orbit and position in space. The US Navy quickly picked up on the significance of this for navigation.

A new system known as Transit followed. With low polar orbits and a 20-30 minute satellite visibility as they passed quickly overhead, it was possible to establish position by using Doppler measurements. The Transit system became operational for military use in 1964 and for civilian use from July 1967.

GPS started development in 1973 with early satellites from 1978. GPS enables position to be derived by trilateration, using broadcast messages of each satellite's position and time. The GPS roll-out was delayed as satellites were due to be launched on the Space Shuttle, which suffered a catastrophic failure in 1986. Notwithstanding, by 1993 a full constellation of 24 GPS satellites was orbiting the earth. The world of navigation was changed forever and there was no looking back. In 1987 the United States Coast Guard announced it would cease funding Loran-C stations outside of the US by the end of 1994.

GPS had wider implications too, Loran-C in Europe was dropped and Transit was rendered obsolete and ceased Navigation service in 1996.The success of GPS also led to calls for a European global navigation system for civil use to be “pursued energetically”.

The first GPS Receivers: Specialist and Expensive

With a price tag greater than the average family home (£50,000 at the time) the Daventry Group’s first GPS receiver was known as XR1.

The main customers were survey (especially rig positioning) and the military.

XR1 tracked one GPS satellite at a time, dwelling on each for about 1 second.

Until 1984 there were only four usable GPS satellites, each in 12 hour orbits, and hence navigation was only possible for a few hours each day. Decca remained as a complement to GPS navigation during this time. For maritime applications, dead reckoning inputs were also used to provide continuity of navigation when insufficient satellites were in view.

Multiple Global Navigation Satellite Systems

Russia had also started work on GLONASS, it’s own version of GPS. The first satellites were launched in 1982, four years later than GPS. GLONASS achieved a full constellation of satellites in the mid 1990’s but declined to just half a constellation by 2003. Urgent action and investment by Russia has now returned the GLONASS constellation to a full compliment of satellites, with more modern signals also being added.

It would be 2011 before the first European Galileo satellite was launched, and a decade later before a full constellation was to be approached. Initial Galileo operation was declared in 2016. As of July 2022, full operational capability of Galileo is yet to be declared.

Meanwhile, in the East, China was working on BeiDou, its own “North Star” satellite system. BeiDou achieved full operational capability in 2020 and has more satellites in orbit than either GPS, GLONASS or Galileo systems.

Complementary space-based augmentation signals were also added progressively, helping to improve accuracy and integrity. Multi-frequency capabilities for civilian users were also added to GNSS and augmentation systems over time.

Commercial Navigation Starts

By 1987 the Daventry Group’s XR3 allowed five satellites to be handled simultaneously (as compared to only one at a time on XR1). This was enabled by the so-called “glue logic” of MC68000 processors coupled with five track channel microchips for each satellite tracked.

In 1990 the XR4 was launched as the Daventry Group’s first true commercial receiver. By this time the GPS constellation was complete. XR4 could track up to eight satellites and had an array of tools for data collection, analysis and even remote management of the receivers.

A “PC” variant was used on weather ships, allowing constellation monitoring and precise timing. XR4 units could also be re-purposed as differential GPS base stations with a simple software upgrade.

Additional Positioning Sources

The Global Navigation Satellite Systems provide excellent accuracy. However, they don’t work well everywhere. For example, so-called “GPS-denied” environments are common, such as deep in buildings, in underground car parks or subways.

Satellite navigation has other challenges: the signals are very low power at the earth’s surface and the civil signals are unencrypted. As such, it’s easy to interfere, disrupt or even “spoof” location in receivers that just use satellite navigation. To overcome these challenges, a range of alternative positioning approaches have emerged. These are regularly used by mobile devices and consumer systems and include positioning using cell phone base stations, Wi-Fi access points, Bluetooth beacons and even technology such as cameras and audio on the device. Information from all these “sensors of opportunity” is blended in a “sensor fusion engine” on the device to provide a position. This approach goes some way to overcome the inherent weaknesses in satellite-only positioning.

Military systems use encrypted signals which are resistant to spoofing but still susceptible to some more sophisticated intentional interference or jamming. Military positioning systems regularly blend high-grade inertial sensors with GPS or GNSS signals towards continuous and trusted positioning.

Improvements Widen GPS Use Dramatically

The 1990’s and early 2000’s represented a revolution in GPS receiver design, driven by a full constellation of satellites and increasing receiver processor power. From 2000 the accuracy for commercial users improved dramatically as the “Selective Availability” intentional signal degradation was switched off by the USA.

The Daventry Group developed the XR series through XR5, 6 and 7. Each evolution added an order of magnitude or more of functionality and capability. For example, the XR6 tracked 12 satellites in dedicated channels with position updates ten times each second and could achieve centimetre positioning.

XR7, in 1999/2001, was the world’s first GPS micro-controller, paving the way to providing a GPS receiver as a block of code rather than a chip which customers would embed onto their own integrated circuits.

Satellite navigation with touch screens was around the corner, both for in-car “PND” (personal navigation devices) and smart phones.

"In the late 1990s and the very early part of this century, a satellite navigation receiver would be called a receiver, not a mobile device. GPS receivers were developed by engineers and used by people with some technical knowledge. The users were often known as expert users rather than consumers”

John Pottle (RIN Director), Navigation News, 2017

Personal Navigation and Smart Phone Positioning

During the 2000’s the transition to an integrated mobile phone with a GPS receiver built-in changed the relationship between consumers and everyday navigation.

The Daventry Group continued to lead global innovation in GPS receivers through this period. Their single-chip GPS solutions could be integrated readily, bringing consumer navigation to the mobile device for the first time.

Notable innovations included the ability of the Navigation Position Engine software to run on the host processor platform. The Measurement Engine chip could therefore be smaller and needed less power: when launched, the GNS7560 was recorded by the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s smallest and lowest power GPS receiver.

In 2006 the Daventry Group became GLONAV and then, in 2008, was acquired by NXP and then became part of ST-Ericsson.

Through the 2010’s other Global and Regional Navigation Satellite Systems came online. The Daventry Group set to and developed a range of multi-GNSS receivers.

The increase in satellites in the sky meant that 20-30 or more satellites were regularly visible from a single place on earth, compared to 8-10 for GPS alone. Each satellite transmitted multiple signals and multiple frequencies, including for civilian use. This presented many challenges for receiver design, requiring significantly more processing.

Users also wanted to navigate in extremely challenging environments for satellite navigation: in urban environments with buildings which obscured a clear view of the sky; and even indoors! This led to the development of multi-GNSS receivers able to operate at lower signal received power levels. Other sensors were also used and blended in a sensor-fusion engine to provide continuity of a PVT (position, velocity and time) solution.

The Daventry Group embraced these challenges with the CG series of multi-radio milti-GNSS chips (also including Bluetooth and FM). In 2013 the Group was acquired by Intel, with the further WCS series of multi-GNSS chips for mobile phones and tablets. The standalone navigation chips in these devices integrated signals from four global navigation systems for the first time (GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and Beidou) and augmentation systems such as Japan’s Quasi-Zenith Satellite System.

In 2019 Apple acquired the majority of Intel's smartphone modem business.